This subpage outlines the path which ERL JOURNAL has taken

– by presenting the INTRODUCTIONS of subsequent volumes and their respective TOPICS.

Each Introduction is built around the WHY-HOW-WHAT sequence and presents you with four components:

the overall IDEA, the ESSENCE of the key problem, the STAGE of ERL FRAMEWORK‘s development, and the volume’s CONTENT

| THE EMOTIONAL DIMENSION OF LANGUAGE AND OF LINGUISTIC EDUCATION Volume 2023-2(10) |

RECOGNISING INTERDISCIPLINARY IMPLICATIONS OF THE AFFECTIVE FILTER

Linguistic education, like practically any other form of education, is strongly determined by affect. Although the entire “story” is far more complex, we might summarise it by saying that if students and teachers find themselves in emotionally convenient circumstances, linguistic progress is easily noticeable, whereas in situations when either of them are experiencing negative feelings or emotions, linguistic efforts are likely to prove simply futile. As implied by the well-known concept of the affective filter, negative emotions – be it fear, anxiety, discomfort and such – act an invisible wall blocking cognition and disable linguistic education. Hence, the teachers’ and – predominantly – the students’ affect either aids or hinders education and it does so in a less or more concealed fashion. On the level of terminology, too, the presence and salience of affect is either explicit or implicit. The former is the case with the said notion of affective filter and others such as speech anxiety, emotional intelligence, willingness to communicate, everyday stressors, etc. The latter is even more extensive, although it tends to be overlooked or disregarded, which can be exemplified by such linguistic concepts as, for example, (a) fossilization, which is mostly defined in cognitive terms and relates to that part of language users’ competence which has become fixed and may fall subject to stagnation – but which results from our natural need of comfort and of social recognition; or even such a traditional term as (b) language performance, which is contrasted against language competence and also viewed through a predominantly cognitive prism – but which, too, is subject to our emotional stance and individual invariably-unstable and internally influential feelings.

Having entered Cycle 2 of ERLA’s trajectory this year, we continue our studies on the affective dimension, focusing – by definition – on the individual student and her/his experiencing of educational reality (in accordance with our Scope Minor), as any form of education remains primarily a personal experience. In Cycle 2 (scheduled for four subsequent years so as to cover four complementary domains) we prioritise the affective domain owing to how it underlies humans’ learning processes and either opens or closes gates to successful education (meaning, too, that our beliefs, actions, and thinking rest upon it). Following this logic, it pays to consider how ERLA’s fundamental premises can be read with the affect as the key educational driver: the way we feel about language shapes our entire identity and understanding of the world (we can simply feel like becoming acquainted with particular subject matter or not). Hence, all education rests on our affective stance, which imposes on teachers the need to skilfully manage their students’ linguistic affect (and prompt them to willingly listen, read, write, and speak), which causes the linguistic affect to merit a special position in education at all levels and in all disciplines.

Our joint discussion of these issues took place at the 6th International Pedagogical and Linguistic ERL Conference subtitled ‘On Emotions in Language Learning and Use’, hosted by the University of Ulm (Germany) on 13-14 June this year – which bore fruit also in the form of a number of papers also included hereunder. Organised around 4 modules – connections, systems, domains, and disciplines, the conference addressed the link between emotions and language on the general level (pertaining to questions such as how emotions relate to language skills, what factors determine our emotional approach to language and its learning, etc.) as well as on more detailed strata (relating to specific theories and methodologies applicable for the link in question, how different educational systems across the globe take emotions into account, etc.). As the conference venue had been chosen owing the main discipline of study of the host (Department of Applied Emotion and Motivation Psychology), the key conference talks additionally concentrated on such affect-related themes as achievement emotions, bilingualism (as a lens to human brains), the role emotional content and psychological context (through the perspective of neuroscience studies), or holistic approaches to the studies of emotions and identity in language learning and use.

This volume of ERL Journal gathers texts (twelve papers, one review, and one report) falling into two sections: on the emotional dimension of linguistic education and on the emotional dimension of language per se – as the consideration of either of them should not be conducted without taking the other into account (otherwise we would end up having no idea what particular affective facets need to be attributed to). The papers present a high degree of diversity in terms of their educational settings, goals, theoretical foundations and methodologies applied. They substantially differ in what aspect they examine, be it the emotional dimension of propaganda in songs, the affective benefits of the impact exerted by literature, brain-based learning strategies, or the emotional intelligence of translators and interpreters. What they all have in common, though, is the far-reaching appreciation of affect and how it determines what is happening inside or outside the classroom. The total interdisciplinary picture to be drawn from all the texts included in the volume is quite straightforward: the greater the extent to which affect is implemented into all forms of language-oriented efforts, the more beneficial effects (among students, teachers, and all other language users) can be anticipated. This role of affect is practically impossible to overestimate and needs to be fostered across disciplines, in which the affective filter – typically and wrongly assigned to linguistic education only – matters a lot.

| THE AFFECTIVE SIDE OF LANGUAGE LEARNING AND USE Volume 2023-1(9) |

LINGUISTIC EDUCATION GETTING EMOTIONAL

Affect comes into play much earlier and much stronger than most language users imagine. Its salience and dominance have now long been recognised by neuroscientists and psychologists, who have stressed that affect not only accompanies but, most importantly and surprisingly, precedes our decisions, determines our choices, drives our perception, and, as such, constitutes a fundamental component of our identities and personalities. In the light of this central position of affect in what we do, it is rather odd or even detrimental that, as recent ERL studies have shown, linguistic education has remained preoccupied with the spheres of actions and cognition far more than with students’ emotions (and beliefs). Even the times of the COVID-19 pandemic (addressed earlier in the sequence of ERL Journal’s volumes) have not brought about any marked change in this respect, although the educational circumstances created by teachers’ and learners’ remote work did offer an opportunity to accentuate emotions (as well as the approach to education and language which all of them hold). In other words – to put it in terms we have applied under the ERL framework, the teaching of languages has still been focused much more on the questions What can students do with language(s)? and How do students understand (the world through) language(s)? than on the question How do students feel about language(s)? (or What do students think of language(s)?). Whilst questions concerning, for instance, using and understanding words, phrases or texts are commonplace, those relating to feelings or views concerning the language elements learnt (be it How do you feel about this sentence? or What’s your attitude to this word?) are in most educational settings few and far between. Not striking a balance between the former (psychomotor and cognitive) and the latter two (affective and axiological) domains stands in stark contrast to contemporary psychological knowledge and can be argued to bring numerous detrimental effects, with a waste of time caused by the non-observance of students’ emotions being only one example of that.

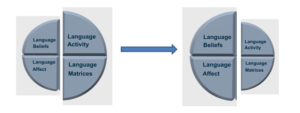

We – meaning the entire ERL framework, particularly ERL Association as ERL Journal’s published – enter into what we have recently come to refer to as Cycle 2, centred around an individual learner and covering the years 2023-2026. Having completed Cycle 1 (2019-2022, ERL Journal’s Volumes 1-8), which have led us to the development and examination of the ERL premises presented by the graphic below, we now adopt pedagogical lenses and put the learner in the ERL limelight, so to speak. This focus of this year’s volumes (9 and 10) is the affective (emotional) side of language learning and use, to be followed in the forthcoming three years by issues addressing – in line with ERLA’s yearly foci – beliefs (axiological domain), activity (psychomotor domain), and thinking (cognitive domain). This four-strand sequence is pedagogically and psychologically motivated: it is after recognition of students’ emotions/feelings and beliefs (values, views) that we can, being well informed on these two underlying strata, properly work on students’ actions (behaviours), knowledge and reasoning. The four-domain perspective has reflected the rationale of the so-called multilateral education and, in the ERL framework, has traditionally constituted the grounds of the (informal) ERL Network (not to be confused with (formal) ERL Association) and its ‘Scope Minor’ outlined at the end of the volume. We encourage all those readers of our journal whose work or interest pertain to any of the strands included in that Scope to share their expertise with us by submitting a paper or by assisting us in any of the other ERL activities – for the benefit of all for whom languages and linguistic education matter.

It is marked interdisciplinarity that ensues from Cycle 2’s agenda: in order to properly examine the affective component of linguistic education, we need to seek the relevant expertise of psychologists, psycholinguists, neurolinguists, and other specialists researching a wide range of issues falling into this strand and including motivation, willingness to communicate, self-confidence, language anxiety, etc. By the same token, throughout the forthcoming years and respective volumes we shall be resorting to numerous fields and subdisciplines that will help us sufficiently account for students’ beliefs, actions, and reasoning, and the further or deeper we go, the more interconnections will follow. Hence, whilst this year (in Volumes 9 and 10) we will be focusing on the central dimension of affect (per se), in the following years and volumes we will be building upon earlier reflections and findings: (in the year 2024) students’ beliefs will be addressed through the prism and in combination with their affective side, (in the year 2025) their linguistic activity will be considered jointly with affect and beliefs, and, finally, (in the year 2026) Cycle 2 will close with the cognitive dimension of students’ linguistic development analysed through the triple filter of affect, beliefs, and language actions.

This volume of ERL Journal gathers papers (and two reports) divided into two sections: ‘Prioritising affect’, where the emotional dimension is – quite explicitly – delineated as the central, underlying, or mentally crucial, and ‘Building upon affect’, where the themes pertaining to feelings and emotions (such as positive anxiety, emotional experiences, or psychological well-being) acquire a secondary, auxiliary, or complementary status. Such a twofold status of affect assigned by this publication can be seen as reflective of teachers’ two types of skills: first, their abilities to appreciate students’ feelings and emotions so as to understand their approach to language learning and use, and, second, their capability of incorporating familiarity with affect (observing and reducing negative emotions, on the one hand, and boosting and capitalising on positive emotions, on the other hand) throughout classroom instruction and beyond. As our Readers will see, the texts included in this volume have been written in various contexts and apply to diversified geographical locations, which we choose to see as a great merit of the volume since it shows affect to be of paramount importance in linguistic education worldwide. We hope to be offering a very pleasant read for the audience, some of whom may be eager to submit to the next volume (also pertaining to the affective side of language and of linguistic education) and/or contribute to the next years’ ERLA foci or ERL Journal’s respective volumes.

| LINGUISTIC CONTEXTS AND DIVERSITY IN EDUCATION Volume 2022-2(8) |

LINGUISTIC CHALLENGES AT A TURBULENT TIME

Turbulent times generate numerous challenges and – sometimes somewhat paradoxically and even beneficially – unravel phenomena that have long remained unnoticed and/or not sufficiently taken into account. Such has been the case with language, which despite being taken for granted in the education of different subjects to various age groups around the world becomes a particularly significant issue and acquires a novel status in particular circumstances, ranging from posing a tool of communication and agreement between different groups and nations to constituting an obstacle inhibiting progress and disturbing achievements in learning and teaching of any given content. As we have been faced with a number of unusually tough challenges in recent times such as COVID-19, a war in Europe, migration, political unrest, etc., educators reflect on the toll which these challenges have taken on the world of education. Apart from the – unequivocally most crucial – tragic “face” of the phenomena in question, there are arise questions which may yield a significant educational fruit such as what effects the recent challenges have had on the linguistic sphere of education, what theories and practices have been applied when dealing with the recent challenges, to what extent schooling has become more linked to other educational contexts, or what our joint experience gained throughout these challenging times implies for the future.

The current turbulence in question has drawn the educators’ attention to the man-language-reality link, with one direct consequence of that strong dependence being that one’s stable positioning in the world rests on language. We “reach” the surrounding world with our language and if we lack necessary linguistic resources do to so, we become alienated and detached from multiple linguistically driven processes and developments. As communication between an individual and a community is mediated by language, our possibilities of normal functioning in the world become radically diminished once our “mediator” cannot do “his” job. By the same token, the transmission of cultural symbols is radically inhibited as well as the process of mutual transformations taking place between man, language, community, and culture. It all means that in the opposite situation, that is in a positive scenario with our communication and self-expression not being violated and reduced – especially in the case of linguistically diverse settings and contexts, our image of the world continues to be – via the process of social mediation – created anew, which broadens not only our language per se, but also our educational possibilities, cognitive horizons, and entire experiencing of the world.

The challenges posed by the recent events have been faced in a comparable degree by both learners as well as teachers, which means that any adjustments made on the level of linguistic education need to be bilateral. In sense, the roles of the two groups have merged in that teachers have had a lot to learn by themselves, too, and to acquire – inter alia – abilities to communicate online, to elicit speech from their students frequently not seen, whilst, learners, apart from providing frequent technical feedback not to themselves but to their online instructors, have had to guide their peers and teachers in different ways of presenting – with words, presentations, recordings, etc. – their knowledge, ideas, methods of solving problems, discussing issues, etc. This novel learning and teaching on the part of all participants of educational processes have encompassed all the dimensions covered by the ERL framework, that is – on the level of the Scope Minor – linguistic beliefs, activity, affect, and matrices, and – on the level of the Scope Major – multiple facets pertaining to schooling, culture, methodology, and personality.

This volume of ERL Journal has an extensive geographical scope and provides its readers with a variety of linguistic settings. It content is well reflected by the titles of the two parts: the first, ‘Diverse linguistic contexts’, including papers and reports addressing such issues as the educational inclusion and success of indigenous children, language policies, language production, migration, and the very sense of educational diversity, and the second, ‘Diverse linguistic means’, containing papers and reports relating to digital literacy and pedagogy, children’s literacy developed by joint application of picture books and toys, music as a means of multilingual education, or linguistic practices employed for English-based specific purposes. The volume closes the first four-year cycle of ERLA devoted to the establishment and initial examination of its four fundamental premises (outlined in the introduction to Volume 7). ERLA’s first cycle – with its eight ERL Journal’s volumes – has covered issues falling within the area of experiencing language and multiculturalism, jointly referred under the ERL Framework as communication (Vol. 1 and 2), linguistic identity (Vol. 3 and 4), linguistic diversity (Vol. 5 and 6), and linguistic diversity (Vol. 5 and 6). Accordingly, the next volume will open ERLA’s second cycle, focused on the Scope Minor mentioned above, with ERLA’s and, consequently, also ERL Journal’s yearly foci pertaining to the four strands named. To remind our readers of the premises upon which ERL Journal has been based, we shall be including the graphic shown on the next page in all the volumes published throughout the second cycle.

Educational Role of Language – 4 Fundamental Premises

|

PLACING LANGUAGE IN THE CENTRE OF SCHOOLING Volume 2022-1(7) |

PLACING LANGUAGE WHERE IT – IN THE WORLD OF EDUCATION – TRULY BELONGS

Educational systems which ignore language as its unequivocal foundation can be regarded as essentially haphazard. Not resting education on language is tantamount to disregard for four basic truths following from one another: (1) Language shapes one’s identity and understanding of the world, (hence) (2) All education rests on language, (hence) (3) Every teacher is a language teacher, (hence) (4) Language merits a special position in education. These four straightforward statements – constituting the key premises of ERL Framework, to which ERL Association as the publisher of ERL Journal belongs to – point to such evident priority of language to be assigned to it that does not apply to any other subject or discipline. They also imply that in order to take them all into account in a sufficient degree, educational systems would need to be practically devised completely anew, which, with education remaining an ongoing process across the globe, may be hard to envisage as plausible for implementation too soon. Yet, it still remains not only possible, but unequivocally necessary if the education of our children and next generations is not to fall behind what we know today about how people learn and how significant a role is played by language in the entire process.

More specifically, what the world of education call been calling for is a thorough reconsideration of students’ development marking the presence of language of four different levels (ranging from its one-off classroom uses to its pivotal role in life-changing processes). First, as we can read on ERL Association’s website, on the instructional level, language needs to be “invited” more into classrooms of different subjects as it has been shown to underlie students’ reality and to enable sense-making, genuine learning, and knowledge construction (or knowledge composition, as I myself tend to refer to the process of language use encompassing, like in music, the fixed and the novel, meaning well-known “pieces” (formulaic language), on the one hand, and authorial or artistic combinations of words and phrases). Second, on the systemic level language needs to be assigned a paradigmatic role in the construction of hybrid educational systems owing to its today-unquestioned developmental potential and interdisciplinary presence providing bases for educational alternatives resting on criticality, equality of languages, plurilingual and transdisciplinary literacy and oracy. Third, on the cultural level, language needs to be viewed as a platform of cultural change and intercultural communication, with cultural diversity resting predominantly on language and the quality of educational systems depending on the level of subject literacy and oracy being the fundamental indicator of effective teaching and meaningful learning. And fourth, on the societal level, language needs to be prioritized as the dominant “player” in civilizational change, with its omnipresence in social life serving international cooperation and formation of learners’ and teachers’ linguistic (culturally-conditioned) identities, and language determining the equalization of educational opportunities and thus fostering democracy.

To serve the language-oriented breakthrough in question, under the ERL Framework we join linguistic and educational “forces” by combining the aims of the two disciplines developing and drawing on interdisciplinary theories and devising joint research and practices. These four ‘joints” have recently provided grounds for the fifth international Educational Role of Language conference, which took place at the point when we were all coming out of the pandemic period and experiencing new – not only technological – solutions in linguistic education. Following a roughly two-year period during which we had all functioned essentially online without the possibility of natural and direct language exchange, we could approach the issue of combining educational and linguistic sciences from freshly developed perspectives and with remote-education experience that had made us crave for renewed face-to-face interaction and for the possibility of hearing and telling new educational and pedagogical “strokes” (as we have recently come to refer to such items of exchange as stories, jokes, riddles, or scientific discoveries). Besides all the hardship and toil brought about by the pandemic, numerous educationally-linguistic initiatives arose from the fact that when teaching online linguists had to reach out to pedagogical concepts in order to make their students more involved, all the educators who had had little to do with language in their everyday work could experience on an everyday basis the salience of language and (frequently faceless) communication.

This volume of ERL Journal tells a part of this ERL “tale” aiming at PLACING LANGUAGE IN THE CENTRE OF SCHOOLING. It covers two parts, one in which focuses on centralising spoken and written text, and the other on centralising language-oriented methods and policies. Jointly, the texts, seven papers and two reports, well exemplify the subject matter, which has always been educationally crucial but which had gained even more weight as a result of the pandemic. In relating to the pandemic aftermath the volume continues the theme undertaken by the previous volume, which was devoted to the notion of linguistic well-being (before, during, and after the pandemic). The volume does not aspire to tell the entire eponymous “story” , but only touches the surface as the problem of how to place language in the center of schooling requires extensive theoretical and empirical studies which we, under the ERL Framework, try to – in our pedagogically-linguistic circle, jointly undertake. We do encourage our readers to join these efforts and to submit texts (as scientific papers or other types of writings) which may help to put language in the at the heart of education, that is the place where it truly belongs.

|

LINGUISTIC WELL-BEING (BEFORE, DURING, AND AFTER THE PANDEMIC) Volume 2021-2(6) |

LIGUISTIC WELL-BEING AS TANTAMOUNT TO EDUCATIONAL WELFARE

Students that do not engage linguistically in classroom activities – for whatever reasons – do not benefit from their education as much as they could. They miss out on numerous developmental opportunities, which frequently occurs at the cost of other students and also teachers themselves, too, since, as a result of such reticent students’ silence, numerous clever ideas and thoughts are lost. The COVID-19 pandemic has been the time during which the aftermath of students’ verbal absence has been experienced on a global scale. It has clearly shown that students lacking in linguistic well-being and remaining consistently speechless throughout their classes and lectures, being hidden behind their deactivated cameras, practically disappear and, subsequently, become likely to fall out of education altogether. In those situations when teachers managed to keep their students linguistically engaged (which tends to imply the latter’s emotional involvement, too), language has served as a kind of glue securing students’ contact with their school settings. However, in all these circumstances where the “glue” in question was missing, students have become passive listeners often preoccupied with other online activities, in the light of which they gradually changed into passive outsiders, taking “advantage” of the fact that they could not be seen. Hence, at the end of the line lack of language and linguistic well-being have meant lack of education altogether.

This heavy reliance of education on language and linguistic well-being has caused teachers to ponder pedagogical phenomena and to reflect on affective and axiological issues much more than they normally do, with the typical focus being on the cognitive and psychomotor aspects of language. From this perspective it can be argued that the pandemic has had its “silver lining” in that it has the potential to mark something of a Copernican turn in how most teachers see the educational role of language and in what facets of language use teachers have come to emphasize in their attempts to maximize their students’ linguistic well-being, which can be presented by the following graph:

As the pandemic has left no-one completely unaffected, under ERL Framework (within which ERL Journal is developed) we have sought our linguistic well-being, too. One of the new ways of keeping its members and other participants mentally sane is productive is the recently introduced (monthly) event called ERL Strokes, the idea of which is to exchange 2-minute “strokes” between different nations, professions, races, or ages, and in this way to foster interpersonal communication and good (but nearly forgotten) old practices of telling stories, jokes, riddles, and sharing interdisciplinary and/or everyday discoveries. The event has served to maintain and boost the participants’ (“strokers’”) linguistic well-being and has been attended by academics and university students, with the two groups sharing the need to communicate and experience new content through all kinds of social occasions. (The term ‘strokes’ has been derived here from Eric Berne’s transactional analysis,, whereby strokes are defined as fundamental units of social action, and used in a wider sense as referring to different types of “verbal pieces” which have something educational and/or entertaining in them and which can be easily be passed from mouth to mouth (and thus t exploit the educational role of language).

Accordingly, ERL Journal’s Volume 6 presents a pool of texts, which jointly constitute a reflection of which conceptual notions have remained in focus throughout the pandemic and how the search for linguistic well-being has proceeded. Specifically, we find papers addressing the emotional facet of online education, pedagogical aspects, preparedness, technological challenges, etc. The reading of papers indicates that the pandemic has come to constitute something of a pedagogical awakening in causing linguists to view reality in pedagogical terms (as well as the other way round). The volume is composed of two parts relating to the linguistic well-being of students and teachers, which is meant to emphasize that fact that issues relating to the eponymous concept pertain to all educational “players”. The papers are complemented by two reports, one written by an academic and one by a student (again – for the sake of balance), both addressing spoken language as the medium particularly meaningful throughout the pandemic. Volume 6 follows Volume 5 (COVID-19 – A Source of Threat or Opportunities for Linguistic Education) in its focus on the pandemic and its educational implications. We do advise our readers to study the content of the preceding volume in order to see the progress of our knowledge and conclusions concerning the impact of pandemic on linguistic education, with Volume 6 offering, as opposed to Volume 5, more questions and viable solutions.

|

COVID – A SOURCE OF THREATS OR OPPORTUNITIES FOR LINGUISTIC EDUCATION? Volume 2021-1(5) |

HAS THE PANDEMIC BEEN A BLESSING OR A CURSE FOR LINGUISTIC EDUCATION?

The pandemic has undoubtedly reshaped the way we now perceive education. It has imposed a need to pursue new ways of learning and teaching, novel (online) educational trajectories, and – maybe most significantly – radically different forms of how we now communicate “at schools” and use our language(s). What is particularly crucial to ERL Journal, though, it can be argued to have had its silver lining in that it has brought closer the two “worlds” of linguistic and educational specialists. The former have come to view their reality in pedagogical terms as they were forced to struggle for contact with their students online and to think of ways in which their interlocutors can best be prompted and turn on their cameras and actively participate in lessons kept remotely. The latter, on the other hand have been – consciously or not – caused to reflect on issues to do with language, be it the gap between language reception and production, elicitation techniques, intralanguage, etc. Hence, the educational world of the two groups in question has substantially changed and been enriched with conceptual and didactic categories which are bound to be of use following the pandemic.

Thinking of the impact of the pandemic even more specifically, we observe that it has generated a wide range of questions intersecting pedagogy and linguistics. Many of these questions which have been posed by students themselves and they prove to encompass all the educational (ERL) domains – be it their reflection along the lines What’s the point of speaking (if I can just be quiet) (language(-)beliefs), How to present in words what my school friends cannot see offline? (language(-)activity), How do the others think about the way I say things online? (language(-)affect), or Can be learn all the subjects just by discussing them through the net? (language(-)thinking). Reflection on these issues has possibly raised the students’ language awareness, especially if their teachers have happened to render such questions and the issues they address explicit in particular classroom contexts. This being the case, we can observe here room for inevitable emergence and amplification of interdisciplinary linguistic identity across and within all school subjects and disciplines. What follows is that the remote education triggered by COVID-19 can be viewed as an opportunity to develop and extend students’ awareness of their linguistic identity on the axiological, psychomotor, affective, and cognitive strata.

Having exerted far-reaching impact on the entire educational world, the pandemic has taken its toll on the ERL Framework and ERL Journal itself just as well. With the ERL (live) Conferences having been put on hold till international gatherings cease to pose any threat to the participants, ERL (online) Sessions have been held, which yielded in due course some of the papers included in this volume. Prior to its publication ERL Association has hosted four online sessions. the last two of them took place in spring 2021 and concerned, respectively, threats and opportunities generated by COVID-19 for linguistic education (the very same title as that of this very volume) and linguistic well-being (which, in turn, is going to constitute the essence of Volume 6 to be published later this year). Although all four ERL Sessions attracted participants from multiple places in the world (and to enable this, each session was scheduled for two days, with the first one being more convenient for European academics, and the other – for those joining from the other hemisphere), most of the attendees reported on their struggle with teaching dominated throughout the pandemic by long hours of online classes and excessive computer work, which has made them less willing or less able to do research and produce as many scholarly papers as they had done prior to the times of the pandemic.

And yet, we have managed to compile this volume, which, despite being shorter than all the four published earlier, partially reflects the course taken by ERL Framework. It strives, as the title implies, to seek balance between the negative and positive effects of the pandemic and reflects a host of issues that COVID-19 has caused us to face on the level of language in education. On the whole, all the texts included in it jointly serve two functions: first, they emphasise the salience of the pedagogical component brought to the fore by the pandemic as noted above, and, second, they outline selected issues appearing relevant to linguistic education at the times when education comes to rest of modern technology and nearly solely online communication. At the same time, we view the set of papers and reports included here as a natural continuation of the eponymous issue of the previous ERL Journal’s volume – (Re-)Shaping One’s Identity with Language, with the pandemic imposing on all academics, teachers, linguists, and students a need to redefines themselves on the educational level and to start using the language(s) they know well in novel ways – through a channel they had not exploited earlier for these purposes, and by the form of Internet interaction which forces them to overcome various barriers they had had, not only technical, but also interpersonal, methodological, pedagogical, and/or linguistic.

|

(RE-)SHAPING ONE’S IDENTITY WITH LANGUAGE Volume 2020-2(4) |

ON THE RECIPROCITY BETWEEN ONE’S LANGUAGE AND IDENTITY

Language learning is a life-changing event with far-reaching individual, social, and cultural consequences. Along with advancing linguistic abilities comes enhanced awareness of one’s identity and development of a (renewed) language self. On the more general level, it determines one’s identification with particular social groups and impacts on educational, social, economic, and cultural processes such as inclusion, acceptance, recognition, and integration. On a narrower scale, becoming familiar with even a single linguistic item opens up new perspectives and thus enriches one’s everyday life experience. In either case, the expansion of one’s identity via language is inevitably a holistic and comprehensive individual experience, cutting across one’s views, actions, emotions, and conceptualisations of the world.

The very existence of linguistic varieties (identities) poses a significant challenge to be addressed by modern educational systems, which – in order to remain relevant and consequently practical, too – need to adopt novel, transdisciplinary approaches and methods of teaching and learning. Such is the case with (Django and Paris’s) concept of culturally sustaining pedagogy (CSP), the emergence of which we have recently observed as a respectful and productive critique of previous formulations of asset pedagogies. As one of the proposals admitting linguistic identities into education, it exemplifies concepts which point out the salience of language not only for one’s multi-faceted development, but also the advancement of education and society as a whole. It is through this admission of linguistic identities that the diversity of linguistic capital is recognised, which is of paramount importance in light of the fact that the linguistic dimension of learners’ and teachers’ identities proves to determine their status, success, and quality of life.

Accordingly, the focus of this volume is on the individual facet, which can be argued to be most directly observable and relevant regardless of one’s cultural and linguistic background. How any language user situates themselves on the level of language underlies how s/he positions herself/himself in the world as a whole, regardless of whether this interdependence is realized by an individual or not. Such an approach to language as shaping one’s identity and one’s self-positioning characterises the interpretative paradigm, whereby individuals interpret reality in their own ways and assign meanings to what they encounter by applying highly personalised systems of concepts, with regard to which they hold their own beliefs, undertake self-imposed actions, and cherish emotions generated through their learning (and/or teaching) trajectories.

Hence the title of this volume – (RE-)SHAPING ONE’S IDENTITY WITH LANGUAGE, pertaining to processes undergoing on several levels. To reflect the overarching character of linguistic experience and its lasting impact on one’s identity, the volume addresses the eponymous issue through the prism of interdisciplinarity, cross-cultural encounters, linguistic quality, and cross-domain intersections. As opposed to the three earlier volumes, the research papers are included in the volume in subsequent parts together with reviews and a report (on the first ERL online Session) to better reflect the volume’s complementarity also on the level of text formats and the experiencing of empirical data or academic readings and activities. Following the two opening volumes of ERL Journal devoted to boosting the educational experiencing of language (2019-1(1)) and enhancing multiculturalism in language education (2019-2(2)), this volume is the second one centred around the concept of identity, with the examination of linguistic dimension having been the focus of the previous volume (2020-1(3)). All the four volumes published so far need to be seen as following from one another and thus to provide a comprehensive picture, which in the volumes to come is to be further developed and addressed from the perspective of hard times, affected by the global pandemic and other phenomena via which our linguistic identity remains continuously reshaped.

|

EXAMINING LEARNER AND TEACHER LANGUAGE IDENTITY Volume 2020-1(3) |

ON OUR ERL PATH TO LEARNER AND TEACHER IDENTITY

Language takes to us spaces we have never “visited” before. The learning (with comprehension) of a new word or phrase opens a gate to an entirely new experience, expanded awareness of the surrounding reality, and greater appreciation of the human limitations and possibilities at the same time. This novel experience is thoroughly personal in that each of us, with a different mental structure, incorporates the new items in a fully unprecedented way, and at every stage of the individual intralanguage, each of us arrives at a unique whole. Hence, the process of incorporating any particular language items reaches beyond the concept of construction, and appears more reminiscent of composing (as in music) in that it consistently implies unknown combinations and constructions which cut across not only different semantic fields, but also multiple disciplines and reality dimensions.

This process of language composing underlies entire education, retains a highly personal character, and drives the formation of learners’ and teachers’ identities altogether. Its significance becomes straightforward once we come to realize how much our idea of other people, their personalities and knowledge, rests on their understanding and use of – first/native or second/foreign – language. Their language identity – understood by us as a highly personalized four-dimensional hybrid encompassing their language views, language activity, language affect, and language matrices – largely shapes all learning and teaching environments and it also determines all learners’ educational (and frequently also later professional) success. Needless to say, this applies to all educational levels and settings, with the linguistic functioning of learners and teachers invariably occurring in the foreground of their work and studies. The process is, naturally, socially- and culturally-conditioned, which in ERL Journal is consistently reflected through its authorship cutting well across country and continent borders.

It is due to the fact that this key position of language across the educational board remains underrated that this volume continues ERL Journal’s sequence – after we have focused on the concepts of experiencing of language in Volume 1 and enhancing multiculturalism in Volume 2 – with the notion of language identity. This volume’s eponymous concept has recently given rise to the ERL online Sessions held by ERL Association, with the first event of this type being organized in the wake of COVID pandemic, during which learners’ and teachers’ identities have been put to a kind of test they had never undergone before. The first session thus concentrated on ‘learner and teacher language identities’, understood wider than ‘language learner identities’ in that whilst the latter (narrower) concept can be paraphrased as ‘the identity of language learners’ and relates to how students situate themselves in the world as language learners only, the former one encompasses entire education (and life altogether) and pertains to how students situate themselves in the world on the level of language, not necessarily with reference to (L1 and/or L2) language education only.

The volume addresses LEARNER AND TEACHER LANGUAGE IDENTITY on several levels, that is on the strata on individuals’ awareness, official documents, educational texts, and didactic practices. In each of these four dimensions the facet of learners’ and teachers’ language identity can be argued to be systematically taken for granted and thus substantially – and detrimentally to all educational stakeholders – essentially neglected. With 9 papers scattered across the four levels named, Volume 3 constitutes an appeal for placing ‘learner and teacher language identity’ in the centre of educational discourse. Its message chimes in with a joint publication issued recently under the ERL Framework under the title ‘In the Search for A Language Pedagogical Paradigm’, “aimed at cohesion and coherence across multiple approaches to how language is and should be implemented into education” (ibidem: 9), in which the concept of same understood language identity of teachers and learners plays a major role. The volume closes with a review of another ERL-oriented publication concerning the ‘educational role of (four) language skills’ across education, followed by a brief report on the aforementioned ERL online Session. We hope that the readers of Volume 3 will share our belief that the notion of ‘learner and teacher language identity’ opens lots of spaces worth exploring.

|

ENHANCING MULTICULTURALISM IN EFL COMMUNICATION Volume 2019-2(2) |

THE WIDER CONTEXT OF THE SECOND VOLUME

The experiencing of language, which was the eponymous issue of the first volume and which acquires both an individual and social character, laid the foundations for ERL Journal. It has prompted us, meaning academics involved in the informal so-called “ERL circle”, to seek what can be referred to as the glottodidactic paradigm, the essence of which is consideration of educational phenomena through the prism of language. Its scope is very wide and implies far-reaching interdisciplinarity and assistance of a large community of researchers including theoreticians of education, applied linguists, psycho-, socio- and neuro-linguists, to mention just a few subgroups. ERL Journal remains open to papers by all of them due to the simple fact that only through their systematic and well-informed cooperation can we get “to the heart” of the educational role of language. By referring to the general goal of those whose interests intersect language and education as “a paradigm”, we convey the view that owing to the salience of language across multiple subjects and disciplines, the world of education can well be studied and advanced by application of terms and methods traditionally associated with language and (especially second) language learning.

We welcome and publish both theoretical and empirical papers. By combining the two directions “from theory to practice” and “from practice to theory”, we strive to examine how theoretical knowledge concerning the importance of language is applied in practice, and, conversely, in what ways educational practice informs theory. Such double lenses we see as reflective of educational reality, where theory and practice need to matter in a comparable degree and where their mutual reinforcement – addressed in ERL Journal on an international scale – can be observed on the level of teaching methods, cultural influences, teachers’ and students’ beliefs, and personal understanding of the learning or teaching of any given subject. It is only through a joint analysis of theory and practice that we can arrive at answers to questions which are crucial for the understanding of the linguistic edge of education such as How does the language of schooling support students’ beliefs, activity, affect, and thinking?; How is the intercultural competence developed through first/native and second/foreign language education?; What implications for research and teaching methods follow from the so-called “linguistic turn”?; or, by definition, How personally relevant is the language employed in educational theories and practices?

All the theoretical considerations and empirical studies published in ERL Journal, the common denominator of which is the authors’ pursuit of the educational position of language, contribute to what we have now come to refer to as the ERL framework. Hence, all the “ERL papers” jointly erect a kind of “scaffolding” which – in accordance with the journal’s mission, which is to boost the position of language in education – may lead to the construction of educational systems upon language and how it is acquired/learnt, used, processed and continuously developed. This aspiration makes us, the journal’s editorial team, open to new proposals of how to bridge the gap between linguistic and educational studies, and necessitates publication of both qualitative and quantitative studies falling within the two scopes outlined in the previous volume. Once this gap has been successfully bridged, we shall start observing solutions which from today’s perspective appear very attractive – that is such educational systems occurring around the globe in which predominant questions concerning education are language-oriented and can be exemplified by the following: How do L1 and L2 interplay with each other and all the other subjects?; How much can students say on particular issues?; What words and expressions do students find useful and which of them do they simply (dis)like? or What do teachers believe their students read for?

This volume, centered around MULTICULTURALISM IN COMMUNICATION, follows and complements the previous one in that the eponymous concept, similarly to the category of (personal and social) experience, co-defines today’s reality of the functioning of language in education. It is omnipresent throughout learners’ and teachers’ developmental encounters, so to speak, and yet largely taken for granted and, consequently, not subjected to scientific studies. For this very reason, it appeared to us that our search for the aforementioned glottodidactic paradigm, theoretically-informed as well as practically-directed, needs to proceed from ‘boosting the experiencing of language’ to ‘enhancing multiculturalism in communication’. We presumed that by theoretical consideration and empirical examination of the two volumes’ eponymous concepts we can best pave the way for narrower issues partaking in the ERL framework. The volume strives to do it as comprehensively as possible with two spectrums making up its four parts, that is offering texts which, first, address multiculturalism “on paper”, on the one hand, and in didactic reality, on the other hand, and, second, pertain to what teachers and students believe in and what they actually experience on the level of multiculturalism. Finally, we also present two reviews of publications which fall within the ERL scopes and additionally enrich our perspective of the multi-dimensionality of language learning and its persistently emotional experience.

|

BOOSTING THE EDUCATIONAL ROLE OF LANGUAGE Volume 2019-1(1) |

WHY ERL VOLUME AND WHY THIS VOLUME’S THEME?

The educational role of language – the journal’s pivotal theme – is a globally meaningful issue. Its salience and worldwide relevance can be well understood and properly appreciated by joint consideration of the following concepts/positions: (a) the so-called linguistic turn, which occurred in humanities nearly 100 years ago[1] and which stipulates a shift of emphasis from speaking about the world by means of language to an opposite view whereby language becomes understood as an act of changes, as a process of harnessing the world in forms of expression and modification of the world; (b) the interdependence between the three spheres[2] – perceptual (constituted by reality experienced by man), subjective (man experiencing that world), and intersubjective (the sphere of meanings worked out by community and mediating the other two spheres); (c) the assignment of meanings, performed continuously on the individual stratum and resulting in the “narrative turn”, whereby language is a medium thanks to which complex internal narrations convey meanings and each of the subjects creates a different type of the narration about the world[3]; and (d) the simultaneousness of our world’s formation and language expressed in that “we ourselves are words (…) words are who we are, they extend from our essence and they define our being. They define our place in the world and they define the world in which we are placed”[4].

The issue in question intersects pedagogy and linguistics and also pertains to other multiple disciplines and subjects which – only if rested upon jointly – can credibly unravel the position of language in education. The degree in which the educational role of language is an interdisciplinary theme leads to two major conclusions: first, it necessitates the involvement of specialists having different – yet complementary – perspectives on it, many of whom can be seen in somewhat bipolar terms, as for, example: educational scientists and linguists, first/native language educators and second/foreign language teachers, theoreticians and practitioners of language, qualitative researchers and quantitative analysts, university academics and primary/secondary school teachers, early education specialists and higher education experts, but also sociolinguists and psycholinguists, syntacticians and phoneticians, speech therapists and language coaches, ethnolinguists, language anthropologists and possibly others; and second, there is a need for a journal combining educational and linguistic studies, which is precisely what the ERL Journal aspires to do. We believe that thanks to the journal filling an important niche, many writers and researchers who has till date struggled with the dilemma as to whether to publish in an education- or language-oriented journal, publish here.

Hence, the ERL Journal addresses the said multi-faceted realm and takes into account the social complexity of the eponymous issue. Published by the International Association for the Educational Role of Language, it reflects encompasses ERLA’s interests comprised of what we refer to as ‘Scope Major’ and ‘Scope Minor’. Under the former, ERL Association – and, as a result, also ERL Journal – focuses (more broadly) on the educational role of language at the level of SCHOOLING, CULTURE, METHODS and PERSONALITY, whereas under the latter – (more narrowly) on language-user perspective by studying language beliefs (what we THINK OF language), language activity (what we DO WITH language), language affect (how we FEEL ABOUT language),and language matrices of reality interpretation (how we UNDERSTAND THROUGH language), with all the four areas complementing and supporting one another. In our efforts to combine eight areas of the two scopes (also referred to as ‘strands’ in the Journal), we strive to retain geographical extensiveness and balance on multiple levels, and to have a reader-friendly and ground-breaking character, with the former achieved by means of an approachable language and the latter by promotion of innovative papers highlighting the educational role of language. Technically speaking, we assume publication of two types of volumes: regular issues covering any one or more of 4 strands of the Scope Major (Module 1) or 4 strands of the Scope Minor (Module 2), and special issues edited by academics providing a template-based volume outline.

This – launch – volume exemplifies the range of issues falling within the aforementioned extensive field and runs across different areas, which, despite seeming divergent, share a lot. In this first volume we emphasise the category of learners’ EXPERIENCING OF LANGUAGE at the level of language content, digital interaction, speaking and writing. We view it as a highly suitable start of our joint interdisciplinary “journey”, following the previous “adventures” in the form of ERL Conferences, ERL Network and ERL Association. The concept of language experience renders it possible to explain in perhaps the simplest form what the ERL Journal is about: it has been initiated to study and share how learners and teachers from across the globe experience the educational position of language. Accordingly, this volume gathers 13 papers by authors from different continents relating to various dimensions of the educational world, that is to language in and outside the classroom, language skills, schoolbooks, and virtual reality. Additionally, the volume includes one review of a book whose interdisciplinary character can be seen as representative of the ERL field, and one report representing the “ERL story” from the position of one of our regulars, who has participated in all the ERL conferences held so far and has also been involved in ERL Journal’s strands coordination. We leave the interpretation of all the papers and the two extras to our readers, whom we also encourage to submit their own papers presenting their own views on the eponymous concept. We hope that the ERL Journal will serve the examination and the position of language in education.

[1] The term was introduced first by Ludwig Wittgenestein in 1921 in his Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung.

[2] as distinguished by Jürgen Habermas in Communication and the Evolution of Society (1979).

[3] as presented by Anna Wasilewska in her discussion “Expansion of linguistic paradigm in studies on childhood and school” published in Educational Role of Language, M. Daszkiewicz, A. Wasilewska, E. Filipiak, R. Wenzel (Eds.), Wydawnictwo Naukowe KATEDRA, 2017.

[4] Likutei Sichos; further developed by Isaac Calvert in his talk at the 2nd ERL Conference in Gdańsk in 2017.